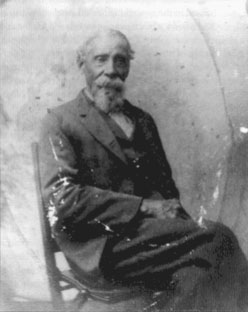

Timbuctoo settler Lyman Epps Sr.,

who stayed at North Elba and

became a close friend of John Brown

One year after John Brown moved to New York, Congress passed the 1850 Fugitive Slave Bill. The law stipulated that anyone convicted of helping runaways could be fined $1000 or imprisoned for six months--for each offense. Blacks convicted of being fugitives would be sent back into slavery. The citizens of Jay, Keene, North Elba, St. Armand and Wilmington met in the Jay Baptist Church and expressed their opposition to this punitive law.

Jay Baptist Church

John Brown returned to Massachusetts and organized the League of the Gileadites so Springfield's terrified fugitive slaves could defend themselves. Before he left, Brown gave strict instructions to his wife and children to "join in resisting any attempt that might be made" upon the Timbuctoo settlers.

Concerning Cyrus Thomas, the fugitive slave who had followed Brown to the Adirondacks, Brown's daughter Ruth said, "We would have all defended him." Cyrus, however, was ready to defend himself. He followed Brown back to Springfield and became one of the more than 40 people who signed the document which created the League of Gileadites.

In 1855, the Browns moved into a home built for them by their son-in-law, Henry Thompson. It has been difficult for historians to find a primary document such as a letter to prove that Brown kept fugitive slaves in his permanent home, and some have concluded he never did. However, Ruth Brown Thompson said her father "never lost an opportunity to aid in every possible way those who were escaping from bondage." And Lyman Epps Jr., the son of Timbuctoo settler, Lyman Sr., said on one occasion Brown brought a fugitive slave to his father's home for the night and returned the next day to take the man to the Canadian border.

When armed conflict between pro- and anti-slavery forces erupted in Kansas in the mid-1850s, Brown went to defend his five sons who had moved there. He engaged in several violent armed raids in "Bloody" Kansas. The contest over whether or not Kansas territory would enter the union as a slave or free state was a testing ground for 1859, when Brown would lead an armed band of white and black men in a raid on the arsenal and rifle factory at Harper's Ferry, Virginia. Brown was captured, tried, convicted of treason and hanged. At his request, he was buried at his North Elba farm. The night before his burial, his body was kept at the Essex County Courthouse.

Essex County Courthouse

John Brown ignited the fuse that exploded into the Civil War in 1861 and ended chattel slavery in 1865. He made the anti-slavery cause a holy crusade for our nation's very soul.

For more on John Brown and fugitive slaves at North Elba, see the Summer/Fall 2007 and Winter 2007/Spring 2008 issues of our newsletter, The North Country Lantern.

The Essex County Courthouse and the John Brown Farm are documented sites on New York's Underground Railroad Heritage Trail. A National Historic Landmark and New York State Historic Site, the John Brown Farm is located on John Brown Road, just south of the intersection with Old Military Road in Lake Placid. For hours of operation, visit the John Brown Farm State Historic Site website.

For information on descendants of John Brown and the most recent research findings, see www.alliesforfreedom.org.

Sources:

F.B. Sanborn ed., The Life and Letters of John Brown, Liberator of Kansas, and Martyr of Virginia (1884 rpt. New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969), 101.

John Brown and Gerrit Smith images, courtesy Special Collections, Benjamin F. Feinberg Library, State University of New York at Plattsburgh.

John Brown Farm, Jay Baptist Church, Essex County Courthouse photos by Laura Sells Doyle.

Louis A. DeCaro, Jr., Fire From the Midst of You. New York University Press: New York and London, 2002), 191.